Women in the ministry and shadow ministry

Authored by Anna Hough (@AnnaC_Hough) of the Australian Parliamentary Library (@ParlLibrary). This analysis was originally published on the Parliament of Australia website.

While the recently-announced Albanese cabinet achieves greater female representation than historical cabinets, Senator Penny Wong is one of only a handful of women to lead portfolios that are not considered ‘feminine.’ Photo credit: Wikimedia/ Crawford Forum.

The recent announcements of the first Albanese ministry and the first Dutton-Littleproud shadow ministry saw both the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition emphasise the number of women on their frontbenches. How much has the gender composition of the ministry and shadow ministry changed, and how significant are those changes?

Prior to the election the 30-member Morrison ministry (comprising the Cabinet and outer ministry, but excluding assistant ministers) included 9 women (30%), while the 30-member Albanese shadow ministry (comprising the equivalent shadow ministers) included 12 women (40%). The proportion of women in the ministry has increased following the 2022 election, while the proportion of women in the shadow ministry has also increased in comparison to the previous Coalition ministry. The new Albanese ministry of 30 includes 13 women (43.3%), while the new Dutton-Littleproud shadow ministry of 31 includes 11 women (35.5%).

Figures 1 and 2 below show the percentage of women in the ministry and the shadow ministry, respectively, after each federal election since 2001. Australian Labor Party (ALP) ministries and shadow ministries are shown in red, while Liberal-National Coalition ministries and shadow ministries are shown in blue.

Source: Current ministry list and the Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Source: Current shadow ministry list and the Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia.

As illustrated in Figure 1, when compared to the new ministries announced after each election since 2001, there has been a significant increase in the proportion of women in the ministry following the 2022 election. Meanwhile, the representation of women in the shadow ministry, although higher than in previous Coalition shadow ministries, has fallen in comparison to recent ALP shadow ministries.

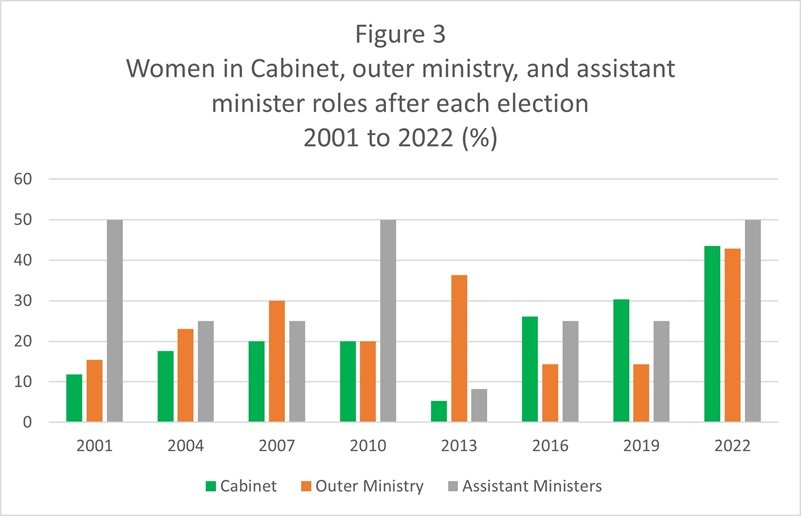

Figure 3 below shows the percentage of women in particular roles—members of Cabinet, members of the outer ministry, and assistant ministers (formerly referred to as parliamentary secretaries)—in ministries after each election since 2001. Figure 4 below shows the same breakdown for women in the equivalent roles in shadow ministries.

Source: Current ministry list and the Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Source: Current shadow ministry list and the Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia.

As set out in Figure 3, over the past two decades women in the ministry have tended to have higher representation in non-Cabinet roles—that is, in the outer ministry, and particularly as assistant ministers—rather than in Cabinet. The same pattern can be observed for women in the shadow ministry and shadow Cabinet as shown in Figure 4. A 2014 study (p. 142) found that women experienced a significantly lower rate of promotion to Cabinet than their male counterparts in Australia, and also in Canada and New Zealand.

However, Australia, Canada and New Zealand have all seen improvements in the proportion of women in their Cabinets since 2014. Women’s representation in Australian shadow Cabinets has also improved during that period. In the new Albanese Cabinet, 10 of 23 members (43.5%) are women, which is a record number and percentage of women in Cabinet. In the new Dutton‑Littleproud shadow Cabinet, 10 of 24 members (41.7%) are women, representing a record number and percentage of women in a Coalition shadow Cabinet (but not for all shadow Cabinets).

The increase in the number of women in Cabinets and shadow Cabinets since 2016 can be attributed to a range of factors. One factor is deliberate decisions by leaders to elevate more women to senior roles. In addition, evidence from 30 European countries indicates that leaders of parties to the left of the political spectrum are more likely to appoint women to ministerial positions (p. 631). The data in Figures 3 and 4 suggests that leadership ‘pipeline’ effects are also in play. If there is a smooth flow through the leadership ‘pipeline’, then having more women in parliament should lead to more women in the ministry and shadow ministry. Likewise, having more women serving as assistant ministers and in outer ministry roles (and their shadow equivalents) should lead to more women in Cabinet and shadow Cabinet. However, it should not be assumed that women ‘flowing through the pipeline’ is a natural and inevitable process.

A 2014 Parliamentary Library analysis of ministerial portfolios held by women found that women had most frequently been appointed to portfolios that have traditionally been considered ‘feminine’, such as those relating to community services, women, aged care, health, and education (p. 23). Fewer women have been appointed to portfolios that have traditionally been viewed as ‘masculine’, such as minister for finance, foreign affairs, defence, or home affairs, or as Attorney-General. Women who have served in those roles (noting that women have also served in related portfolios) include:

Margaret Guilfoyle: Minister for Finance, 1980—1983

Penny Wong: Minister for Finance and Deregulation, 2010—2013; Minister for Foreign Affairs, 2022—

Nicola Roxon: Attorney-General, 2011—2013

Julie Bishop: Minister for Foreign Affairs, 2013—2018

Marise Payne: Minister for Defence, 2015—2018; Minister for Foreign Affairs, 2018—2022

Linda Reynolds: Minister for Defence, 2019—2021

Michaelia Cash: Attorney-General, 2021—2022

Karen Andrews: Minister for Home Affairs, 2021—2022

Katy Gallagher: Minister for Finance, 2022—

Clare O’Neil: Minister for Home Affairs, 2022—

To date, only one woman, Julia Gillard, has been Australia’s Prime Minister. Australia is yet to have a female Treasurer, unlike, for example, the United States of America or Canada (where the equivalent roles are currently held by women), or New Zealand (where the equivalent role has previously been held by a woman).

Read more from Anna Hough:

Factoring in women: Trends in the gender composition of state and territory parliaments

Power in representation: Trends in the gender composition of Australian Ministries

Ms. Representation: Trends in the gender composition of the Australian parliament

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury