Understanding the links between women, violence and poverty for Anti-Poverty Week

Anti-Poverty Week is an event held every October to raise awareness and understanding of the causes and consequences of poverty in Australia, and to encourage action to end it. In today’s analysis, researchers at the Life Course Centre (@lifecourseAust) are highlighting the links between women, violence and poverty, and the structural inequalities that must be addressed to stop it. A summary of this analysis is presented here by Dr Alice Campbell (@ColtonCambo) and Professor Janeen Baxter (@JaneenBaxter7); you can read their full report here.

Anti-Poverty Week runs from 17-23 October this year.

Domestic and family violence is a growing problem in Australia and the advent of COVID-19 appears to have escalated incidences.

Financial distress and violence are correlated for Australian women. Photo by Viki Mohamad on Unsplash

Data from the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) in 2020 showed that amongst Australian women who reported violence since the start of COVID-19, 65.4% experienced an increase in the severity or frequency of domestic violence or experienced it for the first time.

Building on this initial study, the AIC this month released further research on women’s experiences of first time and escalating violence during COVID-19, or what it terms the “shadow pandemic”.

Rising rates of violence and sexual harassment against women, including high-profile accusations within Parliament House, led to large women’s marches across Australia in March this year, followed by the convening of a National Summit on Women’s Safety in September.

In the lead-up to this summit, we collaborated with the organisers of Anti-Poverty Week to produce research analysis focussed specifically on the associations between experiences of violence and financial hardship for young Australian women.

This research clearly demonstrates that violence pushes young women into poverty at rates much higher than for women not subjected to violence.

Identifying how violence and financial hardship overlap for young women is critical to a better understanding of women’s trajectory across their life course.

The prevalence of violence against young Australian women

Using data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH) collected in 2017, we first highlighted rates of violence and abuse amongst young Australian women.

Amongst young women aged 21-28 years:

14.4% had experienced some form of abuse at the hands of a current or former partner in the previous 12 months – this includes physical, emotional and sexual abuse, coercive control, harassment and stalking.

4.6% said they had been the victim of unwanted sexual activity in the previous 12 months.

3.7% had experienced at least one form of severe abuse at the hands of a current or former partner in the previous 12 months – this includes being threatened or assaulted with a gun, knife or other weapon, being locked in a room, and being choked.

The links between violence and financial hardship

We then examined the association between violence and financial hardship for these women, finding those who experienced violence or abuse were much more likely to be in financial hardship – by two to three times the rate of women who do not suffer violence.

Amongst young women aged 21-28 years in financial hardship, there were:

More than double the rates of past-year unwanted sexual activity (9.4% vs 4.0%)

Almost double the rates of past-year partner abuse (25.3% vs 12.9%)

More than triple the rates of past-year severe partner abuse (9.3% vs 2.9%)

Figure 1: Rates of past-year abuse amongst young Australian women by financial status

Violence moves women into poverty

Finally, to further extend our investigation of the association between an experience of violence and subsequent financial hardship, we examined the rates of women moving into financial hardship following violence or abuse. This provides a more robust analysis as it focusses only on women not in financial hardship in the year prior.

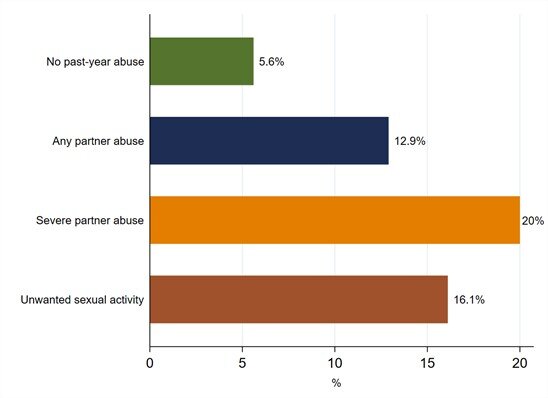

Amongst young Australian women aged 21-28 who were not experiencing financial hardship in 2016, the risk of moving into financial hardship in 2017 were:

More than triple amongst women who had been the victim of severe partner abuse in the past year (20% vs 5.6%)

More than double amongst women who had been the victim of any partner abuse in the past year (12.9% vs 5.6%)

Almost triple amongst women who had been the victim of unwanted sexual activity in the past year (16.1% vs 5.6%)

Figure 2: Rates of moving into financial hardship amongst young Australian women by past-year abuse

*These analyses on young Australian women aged 21-28 years of age use data from Wave 5 (2017) of the 1989-1995 birth cohort of women from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH). Women were categorised as experiencing financial hardship if they reported they had been “very” or “extremely” stressed about money in the past 12 months AND they said that it was “difficult all the time” or “impossible” to manage on their current income.

Women more likely to experience both violence and financial hardship

Separate analyses, based on data from the 2019 Wave of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, also reveals gendered outcomes in experiences of violence and financial hardship. These include:

61,314 Australian women aged 15-24 have experienced moderate-to-very-high levels of financial hardship AND physical violence in the past year.

Among those aged 15-24 years, women are 3 times more likely than men to have experienced both financial hardship AND physical violence in the past year.

So, what can be done?

Governments in Australia continue to invest in programs to address violence against women, including new investments since COVID-19 in helplines and counselling.

COVID-19 has also created new opportunities for agencies to respond to issues such as domestic and family violence with innovative, fast-moving partnerships, such as those seen between police and health departments.

Anti-Poverty Week in 2021 is highlighting two key areas for reducing poverty in Australia – the Raise the Rate For Good (social security increase) and Everybody’s Home (more social housing) campaigns. These are both important issues that, if addressed properly by governments, will help to better support women who experience violence and financial hardship.

But to enact real change, it is critical to turn attention to the underlying causes of violence against women. These causes include outdated institutional settings and constraints that perpetuate gendered disadvantage and heighten the risk of violence against women. Through this lens, we need to acknowledge and address domestic and family violence as a gender-based problem.

Addressing gender inequality

It was pleasing to see that the issue of gender inequality was recognised in the final statement from delegates following the National Summit on Women’s Safety, which will inform the next National Plan from the Australian Government to end violence against women.

While this statement covers the importance of prevention, intervention, response and recovery, it also highlights that: “achieving gender equality is key to preventing violence”. Summit delegates’ priorities include the need to: “support gender equality and address the complex intersection of gender inequality with other forms of discrimination, inequality and disadvantage.”

Overall, the prevalence of violence against women in Australia suggests that the problem is not just the effect of a ‘few bad apples’. Violence is endemic, and we therefore need to not only provide support for women experiencing violence but also to address the roots of violence – roots that we believe lie in gender inequality and continuing gender power imbalances.

In Australia, institutionalised gender divisions of labour in the home and at work continue to disadvantage women. Government policies often focus on women rather than gender when what is required is a wide-ranging, whole-of-community approach that encompasses broad policy reform across all settings.

As highlighted in the summit delegates, statement, this also includes listening to, engaging with, and being informed by diverse lived experiences of victim-survivors, who are crucial to informing the development of policies and solutions and understand what work. There is also a critical role for high-quality research, data and evaluation to inform continued investment and program improvements.

Data from the World Economic Forum shows Australia is going backwards on many indicators of gender equality. Defining some jobs as ‘women’s work’, uneven family responsibilities, paying women differently, and ignoring unpaid care work, manifest in many poorer outcomes for women over the life course.

By challenging the outdated gender narratives that persist in these settings, we can reimagine and transform our institutional settings and rules to help reduce and prevent violence against women in Australia.

Dr Alice Campbell is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow and Professor Janeen Baxter is the Director at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (the Life Course Centre). They are both based at the Institute for Social Science Research at The University of Queensland.

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury