From Tightropes to Gendered Tropes: A comparative study of the print mediation of women Prime Ministers

In order to truly represent Australia in all its diversity, we also need greater diversity in our politics. Evidence shows that increasing female representation has a very real impact on the legislation that is raised. In Australia, however, while the numbers of women in politics is slowly inching upward, many women have said that engaging in politics comes at a cost seldom borne by their male counterparts: Consider, for example, Nova Peris’ recent comments on the racial abuse she endured, or the slander endured by Senator Sarah Hanson-Young.

For International Women’s Day, in today’s post Blair Williams (@BlairWilliams26) of Australian National University provides an overview of her research into the way women Prime Ministers are portrayed in the media, how that denigrates their authority and capability, and the negative impact it is having on increasing female political representation.

Two days before my seventeenth birthday, Julia Gillard ascended to the prime ministerial role to become Australia’s first woman in the top job. Her ascension was simultaneously greeted with enthusiasm, albeit brief, and a wild media backlash that highlighted her gendered difference to a position that has only ever been taken up by men. The next three years of her prime ministerial term coincided with my entry to adulthood and, more specifically, womanhood.

During this time, however, the widespread misogyny and sexism that Gillard experienced became only more incessant and vitriolic. This treatment of our first woman prime minister left a deep impression on me and many other Australian girls and women. It demonstrated that women, and especially women in power, are perceived in a negative light, and it revealed that we must adhere to social norms and gendered expectations or risk a similar fate.

On my twentieth birthday, Gillard was deposed. It was the end of a short era that many felt had been marred by misogyny. I was extremely upset to see our first woman prime minister be treated in this manner, but also inspired me to further explore this issue as part of my PhD studies.

Above all, I sought to answer the following questions: How did mainstream print media in other countries portray women political leaders? Was the unrelenting gendered media coverage of Gillard isolated to Australia? Or was this a more widespread phenomenon?

I focused on five women prime ministers, including Gillard, in English-speaking countries with a Westminster system: Margaret Thatcher 1979–90; Theresa May 2016–19; Jenny Shipley 1997–99; and Helen Clark 1999–2008. I look at newspapers because, despite the rise in social media and online news, newspapers still have power and influence as they play a regulatory role that sets the daily news agenda. I chose newspaper articles from the first three weeks of each leader’s prime ministerial term because I wanted to examine how the media directly respond to their ascension. I analysed a total of 1039 articles.

I not only wanted to expose how the media emphasised gender in the reportage of each leader’s prime ministerial ascension, but also to examine how media actors deploy such coverage in their role as a ‘regulatory power’ capable of reinforcing heteronormative gender norms and stereotypes that can impact all women.

The central argument underlying my thesis was that the media rely on and reproduce these gender norms and stereotypes in their coverage of women prime ministers. But what did this look like?

Through my research, I identified a heavy reliance on what I call ‘gendered tropes’. I use this term to refer to common or overused themes recurrent in coverage of women leaders and associated with gender norms and stereotypes that reinforce the existing gender order, i.e. patriarchy. Neither journalists nor newspapers are necessarily aware of their reliance on these tropes, as they reflect how our society subconsciously views women, especially women in power. I identified five over-arching tropes present across the reportage of all five leaders.

Gender and Femininity Trope:

Men are regarded as the norm for political leadership while women leaders are viewed as ‘other’ and therefore constantly marked by their gender. This is evident in the frequent use of qualifying terms such as ‘female’, ‘woman’, ‘lady’, ‘wife’, ‘girl’, etc – e.g., ‘woman Prime Minister’ or ‘female’ leader’. Men, on the other hand, are simply described as ‘Prime Ministers’ and ‘leaders’. I also found many metaphors that played on societal stereotypes of femininity. For example, all five leaders were often depicted as schoolgirls or headmistresses keeping their male colleagues in line, housewives and housekeepers who cleaned up parliament, or sexual dominatrices and barren emasculators.

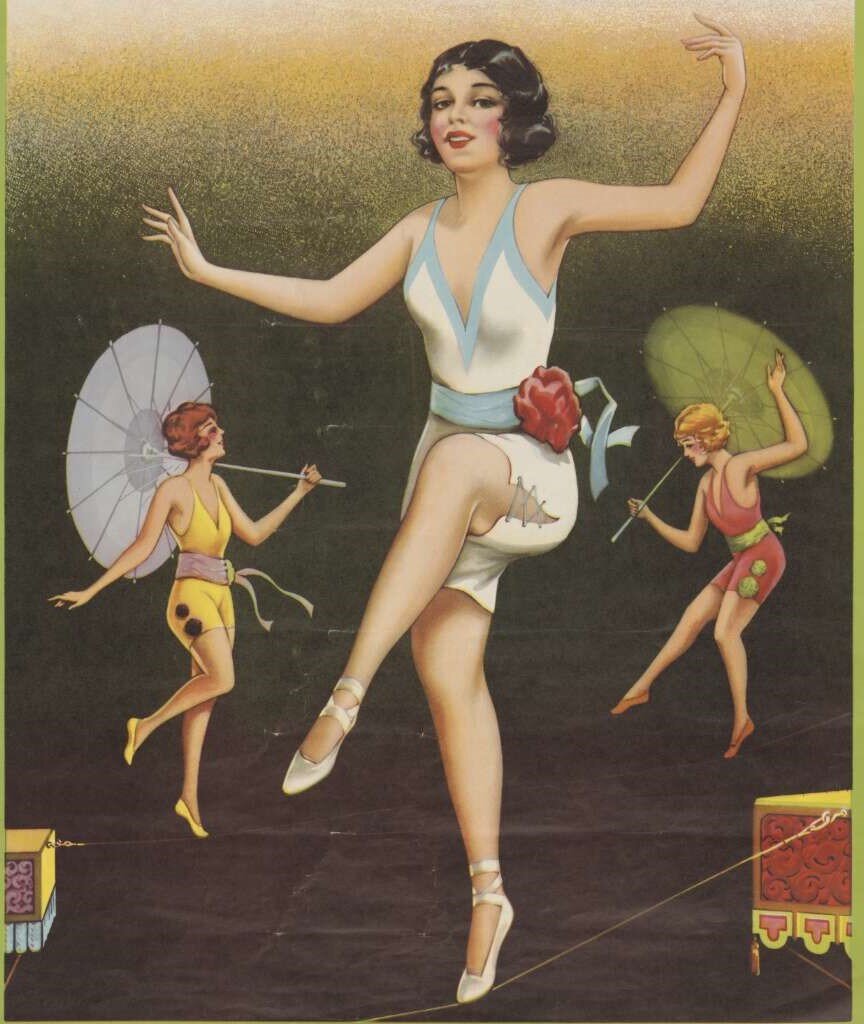

Appearance Trope:

When will women in politics cease to be a spectacle? Image credit: detail from Ivan Brothers International Circus poster, National Library of Australia.

An emphasis on physical appearance, to the extent that a woman leader’s body is delegitimised, deconstructed and segmented into parts, such as hair, skin, clothes, figure, etc., to emphasise their difference from white heterosexual men. The media often assessed a woman’s fashion as if they were celebrities on a runway or used their appearance as an indicator of political performance. For example, many articles speculated that Gillard was obviously preparing to challenge Kevin Rudd because she had changed her hair colour just days before!

Family Trope:

A preoccupation with marital status and family relations, with a particular emphasis on whether a woman is married and has children. Such emphasis on women leaders’ families and personal lives ensnares them in a gendered double bind, inviting judgement about whether they should or shouldn’t have children, how they should parent, whether they should sacrifice their careers or, if they don’t have children, whether they are aren’t ‘real women’ or are unrelatable to the electorate.

First Name Trope:

Instead of using their titles and surnames, as is the case with male leaders, the media instead use women’s first names, sans title, thereby delegitimising them as leaders. Names are a key indicator of social position and relations – those who enjoy higher status are given a more formal title and generally not addressed on first name terms, while those with a lesser status are referred to more informally. For example, Thatcher was often referred to by the nickname ‘Maggie’, particularly in the tabloid press, while Gillard’s first name was often the base of puns used in headlines, such as The Australian article titled ‘Et Tu Julia’.

Thatcher Trope:

Measuring the performance of a woman politician against the career of the UK’s first woman prime minister, and thereby generalising women political leaders as a homogeneous category. Even Gillard – a Labor-left leader – was compared to Thatcher and labelled a ‘Red Maggie’! The fact that a standard of comparison has to be sought marks women as different from their male colleagues, who are generally considered on their own merits or, if they are compared to a previous politician, it’s in a favourable light/to establish a ‘lineage’.

Why does this matter?

Despite more women entering politics, even the upper echelons of politics, my PhD research demonstrates that the media continue to focus on their gender, appearance and personal lives. This can have an insidious and ongoing effect, constantly forcing women to think about how their appearance, relationships and personal lives are portrayed – things their male counterparts rarely, if ever, have to consider. As a result, they often engage in self-limiting behaviours in an attempt to take control of their media portrayal, seeking to create a public persona that is not too emotional or too angry or too fashionable, or not fashionable enough. Yet by doing this, they risk denigration as cold, robotic and aloof, and might find it more difficult to ‘click’ with the electorate. May is just one example of this, often labelled as cold and robotic and even ridiculed as a ‘Maybot’ by some of the press.

Such gendered, sexist, even misogynistic portrayals of women politicians, especially political leaders, can also have what is called a ‘bystander effect’ on ordinary women, impacting their self-worth and even their own leadership and political aspirations. As bystanders, women experience sexism indirectly through watching it on their screens or reading it in newspapers, and they are still negatively affected despite not being the target.

While the bystander effect can be noted in both men and women – as it shapes gender norms and assumptions – women are more acutely affected. Just witnessing the sexism that these leaders experienced daily can decrease self-esteem and career aspirations. Sexist media coverage deters women from entering politics because it reinforces traditional and stereotypical gender roles and demonstrates the relentless critique and abuse they will endure if they choose this path.

We are already seeing the ramifications of this. My previous research found that women were less likely to pursue their political and personal leadership aspirations because of the gendered media coverage of Gillard. A 2017 study found that zero per cent of women aged 18-25 wanted to pursue a political career. Zero per cent.

Why would girls and young women want to enter politics when they see what women politicians have to face? And this research doesn’t even consider the additional prejudices faced by women who aren’t white, cisgender, heterosexual and able-bodied! Furthermore, this comes at a time when we need more women – particularly young and diverse women – in parliament. Not only to achieve parity but to provide diverse views and experiences that represent all of Australia, not just those white men in suits and blue ties.

When the media present the most privileged and powerful women in our society in a gendered, even misogynistic manner, then what messages is that sending to women who are not nearly as privileged? What messages are these women absorbing?

This kind of gendered media coverage, only becoming more frequent, needs to change. We need to critically engage with the media and analyse the messages they’re communicating about gender and how they’re reinforcing gender norms and gender roles through their coverage of women in politics. How do they treat women in power? How does this differ in the way they report on men in power? What gender stereotypes are they relying on and reinforcing?

My gender tropes framework makes it easier for women and women politicians to identify and call out sexism. It provides a clear categorisation of what constitutes gendered coverage, and shows those employed in the mainstream media what not to do in their coverage of women politicians and political leaders. Take, for example, the below article published during the 2019 NSW election and covering NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian’s win:

An example applying the gendered tropes to a news article.

We can’t stop this coverage alone. Journalists need to change the way they report on women in politics or we’ll see a similar fate for our next woman prime minister. When journalists report on women in politics, they could do a quick test to see whether they rely on gendered stereotypes by replacing their subject’s name with a male name, and female pronouns with male pronouns. They can reflect on whether it sounds different, weird or jarring. And, if it does, is it because they’re relying on gender stereotypes that they’d never use in coverage of male politicians? If so, then it needs a re-write so that the article doesn’t reinforce gender stereotypes that delegitimise women politicians while negatively impacting women who witness their treatment.

To make change we need to put pressure on the media by questioning the gender norms and stereotypes they reinforce. We need to keep on fighting, because the path to progress is not linear or a given but is achieved through constant struggle and action!

You can read more about Blair Williams’ research at Women’s Agenda and Triple J Hack.

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury @GoodAdvocacy