Explainer: Why JobSeeker is below the poverty line, and why it matters for gender equality

Gender inequality takes many shapes, embedding into systems and structures in ways that may be hidden. In today’s analysis, Policy Whisperer Susan Maury (@SusanMaury) and Lily Gardener of Good Shepherd Australia New Zealand (@GoodAdvocacy) and Frances Davies of the National Foundation for Australia Women (NFAW) provides a thorough analysis of how Australia’s social security settings, by maintaining the sole use of the CPI in most income support payments is disproportionately exacerbating poverty for women. This analysis is part of the NFAW (@NFAWomen) Gender Lens on the Budget series, drawing on the Indexing analysis, as well as on Good Shepherd’s submission on the adequacy of the Newstart Allowance. This is a companion piece to The gendered nature of JobSeeker.

For people reliant on JobSeeker, the ‘basket of goods’ keeps getting smaller and smaller. Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels

There has been plenty of chatter about how the JobSeeker Payment (formerly the Newstart Allowance) is inadequate. ACOSS’ #RaisetheRate campaign pointed out that there has not been a real increase in this payment since 1994 – until the Morrison Government approved a $50 per fortnight increase this year (which is still inadequate). Why is this the case when payments are regularly adjusted – and does it matter for a payment that’s designed to tide people over between jobs?

The indexation process is the crux of the problem

Most income support payments are adjusted for cost of living twice yearly, in March and September. The JobSeeker payment is indexed to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which monitors a generic ‘basket of goods’ for price increases across a broad range of items. The CPI includes 11 major groups of expenses, including food and (non-alcoholic) beverages, housing, transportation, education, clothing, alcohol and tobacco, communication, recreation and culture, clothing and footwear, and insurance and financial services.

This approach has two main deficiencies: it fails to differentiate between essential and discretionary expenditures, and it fails to reflect the true changes in the cost of living.

Differentiating essential and discretionary expenditures

It matters that the CPI doesn’t differentiate between types of expenditures. The ‘basket of goods’ identifies an average cost increase but fails to differentiate essential services (such as rent, food or utilities) from discretionary costs (such as clothes, leisure pursuits or travel). As a consequence, it unfairly disadvantages people on income support, because a greater percentage of their income goes to essentials (see Dufty, 2012, p. 2).

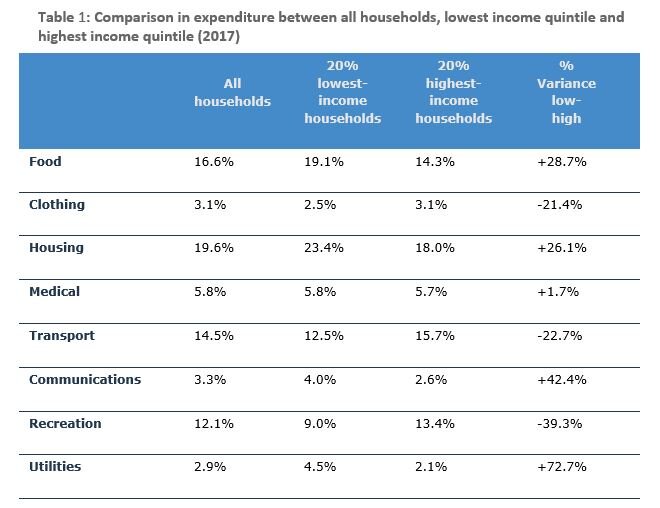

The graph below demonstrates why the CPI is not in fact representative of cost-of-living increases for households with restricted finances. For example, the most disadvantaged households spend nearly 30% more on food as a percentage of overall expenditure than the highest income households, 26% more on housing, 72% more on utilities and 42% more on communications. Conversely, these households spend 21% less on clothing and nearly 40% less on recreation.

Source: Jericho, G. (2017), based on the ABS Housing Expenditure Survey data (2017).

The only expenditure that is comparable is medical, and this may be in part due to a socialised medical system and in part due to the poorest households foregoing medical treatment (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018). This is a likely explanation, with evidence showing (then) Newstart recipients report poor health at 6.8 times the rate of wage earners, while being at 1.5 to 2 times increased risk of hospitalisation (Collie, Sheehan & Mcallister, 2019).

Data collected in 2019 indicates that essential goods are experiencing inflation at a higher rate than other consumer goods and services. Since the end of 2013 the overall consumer price index has increased 10.4%. However, the cost of essential goods – those items which make up most household expenses for low-wage households – are rising at more than twice that rate. For example, education-related costs have risen nearly 25%, childcare is up 26.7%, medical/hospitalisation costs are up 36%, electricity is up 12% and gas has risen 16%. Perversely these expenses are largely government regulated (Wright, 2019). The ABS confirmed this is an ongoing trend when in May of this year they reported that non-discretionary (essential) items experienced 43.8% inflation between 2005/06 and 2020, while discretionary items minus tobacco (which is deliberately hyper-inflated) only rose 18% across the same time frame.

Changes in wages matter

Figure 2. Source: Graph created by the first author using ABS data as reported by the Melbourne Institute.

The CPI also fails to maintain its real value because it does not consider changes in wages – a shortcoming which pensions rectify. The Melbourne Institute tracks changes in both the CPI and the Henderson Poverty Line from 1973/74, when they were equivalent, to now. Sadly, the poverty line would actually be a better indexing system for people on JobSeeker. The latest quarter shows the CPI has lost nearly 80% of its value compared to the poverty line (see Figure 2).

To better reflect real changes in cost of living, an indexation system must include:

1. a weighted indexing that preferences essential costs for lower-income households, and

wages growth.

A problem with a solution

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2019) has already resolved the problem of a weighted index, by creating a new index in 2009 called the Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index (BPLCI). This is a sub-set of their Selected Living Cost Indexes (SLCIs), which examines the differential impacts of price changes in various goods and services for different household types: employee households (primary income source is from employment); age pension households; other government transfer recipient households; and self-funded retiree households. The PBLCI specifically examines the impacts of price changes on households that are dependent on income support:

The PBLCI represents the conceptually preferred measure for assessing the impact of changes in prices on the disposable incomes of households whose income is derived principally from government pensions or benefits. In other words, it is particularly suited for assessing whether the disposable incomes of these households have kept pace with price changes. (ABS, 2019, emphasis added)

For example, the ABS calculations reveal stark differences in the percentage of household income that goes towards housing – just under 15% for employee households compared to almost 24% for PBLCI households (Ibid.)

The Age Pension has kept pace with true changes in cost of living because it is indexed to real changes in purchasing power. This practice is due to the analyses and recommendations put forward by the Harmer review (Harmer, 2020). Importantly, the review was limited to the pension payment only, although the author did demonstrate how using the ‘plutocratic’ CPI was quickly reducing the true value of the Newstart Allowance.

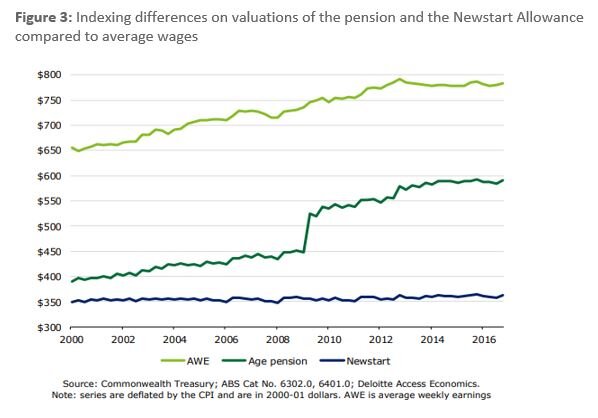

Source: Deloitte Access Economics, 2018.

Including a wage index is critical to ensuring income support payments rise commensurate with true changes in the cost of living (Deloitte Access Economics, 2018). Specifically, using the correct index will protect the real value of payments, while benchmarking benefits to the Male Total Average Weekly Earnings ensures there is protection of the standard of living that those payments represent (Lewis, 2015).

The graph in Figure 3 demonstrates how poorly calculated indexing left the (then) Newstart payment well behind the Age Pension, when in 2000 there was less than $50 separating the two payments.

The Australian Government has been called out on its low levels of unemployment benefits just this week by the OECD, which specifically called out the indexation process as inadequate.

Why does this matter to women?

The government has stated that it deliberately keeps the unemployment benefit low to encourage people into work. In a debate over proposed changes to payments in 2014, this strategy was described thus:

“[unemployment payments] are designed to encourage participation in paid employment – through low payment rates that provide a clear financial incentive to work and through strict participation requirements as a condition of eligibility, forcing recipients to look for work and undertake training/education to boost their employability.”

This may be an effective method when considering people who are genuinely ‘jobseekers’ (although that assumption is also up for debate), but merely calling someone a jobseeker does not make them one.

While the vast majority of people receiving an unemployment payment used to be young men, currently only one in six recipients are men under the age of 35. Several key policy changes in the social security portfolio over recent years have made significant changes to the demographics of people on the unemployment payment. This means women with complex barriers to meaningful employment are being forced onto a payment that was designed to be a short-term buffer between jobs for young men. By maintaining the sole use of the CPI in most income support payments – a deliberate policy decision to erode the value of the payment over time – poverty is being exacerbated for many women and their children.

In Australia, the social security system is a key driver of gender inequality. The system settings fail to account for women’s differential employment pathways compared to men, their disproportionate burden of unpaid caring work, the gendered experience of domestic violence, and the ways that older women in particular are discriminated in employment.

The Coronavirus Supplement (provided last year effectively doubled income in many households reliant on the JobSeeker payment) and the relaxation of mutual obligations due to the pandemic created an adequate and supportive social safety net. Research indicates that physical and mental health improved, time spent in studies and engaging with paid employment increased, and people were able to envision and plan for their long-term financial security. If the Federal Government is truly interested in supporting women into financial independence, they should reconsider these harsh policy settings.

Read more analysis from NFAW:

The gendered nature of JobSeeker

Working from home: Opportunities but also risks for supporting gender equality

Building Australian infrastructure: What works for women?

Beyond the rhetoric: What will the Federal Budget really mean for gender equality?

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury