Restorative justice: Can short-term politics align with long-term juvenile justice policy?

David Moore is President of the Victorian Association for Restorative Justice.

In the #Longread article below he looks at the impact of 'tough on crime' approaches to youth justice in Australia and how restorative justice – "not some warm-hearted-but-soft-headed notion" – offers to resolve the apparent conflicts between short-term politics and long-term policy in youth justice.

The article looks particularly at the Victorian justice system in recent years, where more punitive policies have sparked a spiral of issues for individuals and the system, and also where restorative models are offering real hope.

***

David Moore writes:

Youth Justice remains in the news around Australia.

Tabloids and talk-back propose simplistic solutions to complex problems. Besieged politicians find it hard to resist gesture politics, given the short-term commercial and political logic that anger in response to public fear sells papers, raises ratings, wins votes.

Unfortunately, in the medium- to long-term, angry responses to public fear produce deeply illogical, counterproductive social policy.

Longer sentences for young people increase the likelihood that they will reoffend. So punitive youth justice policies make communities less safe. Policy makers know this, but struggle to resolve an apparent conflict between short-term politics and long-term policy in youth justice.

A recent Jesuit Social Services Justice Solutions report provides many examples of effective international youth detention facilities that deliver low rates of reoffending after young people are released. These facilities tend to be small and home-like, with a high ratio of staff to young people.

They apply a therapeutic and developmental philosophy, and provide staged transition back into local communities. But this sort of arrangement is apparently un-Australian. Large youth detention centres are a key part of Australia’s State and Territory youth justice systems, and an example of path dependence in social policy.

A new youth detention facility planned for Melbourne will double the state’s capacity to accommodate young offenders, and there will be a temptation to fill it, against international evidence of best practice.

Fortunately, behind the bipartisan “tough on crime” talk, some more complex and constructive developments are underway. Patient, thoughtful work is promoting recovery for victims of crime and for offenders. That work is promoting social reintegration, rather than increased stigmatisation, social disconnection and institutionalisation, and reducing crime. It focuses on working with people, rather than doing things to or for them.

But it is difficult for individual governments to take credit for success that results from the collective efforts of dedicated workers across a whole justice system, over many years. It is apparently even more difficult to articulate the coherent, integrated policy needed to sustain this sort of reform, or to describe how mutually supporting programs create virtuous circles, where each improvement supports other improvements.

These virtuous circles tend to become visible only by seeing common themes across many programs.

It’s certainly easier to find examples of “hasty and uninformed policy” feeding a vicious cycle.

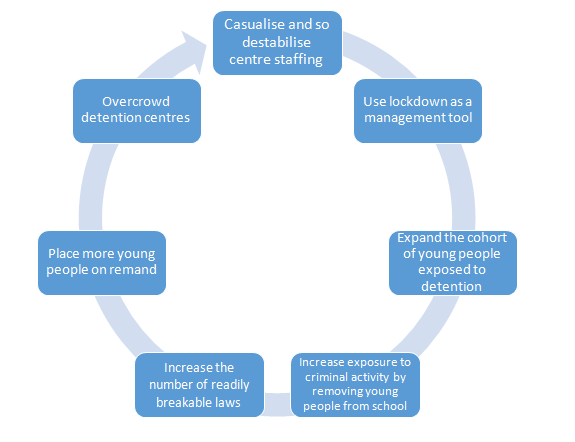

A vicious cycle in Victoria

The former Victorian Coalition government fed such a cycle by changing the Bail Act in 2013, making it an offence to break a condition of bail. The Parkville and Malmsbury detention centres began to fill with remandees, who typically waited months before attending court. The Coalition then gave government school principals more power to suspend or expel students, and many of these students subsequently appeared before the courts and spent time in detention.

The demographic of the inmate population changed, and resultant restlessness contributed to rioting. Deteriorating circumstances reinforced problems with staffing: turnover, casualisation, absenteeism, inexperience, and shortages.

After the sense of crisis continued under the Labor Government for another two years, responsibility for youth justice was transferred, in April 2017, from Human Services to the Justice Department. There may yet be administrative and other advantages in this move, but the short term emphasis is on safety and security. Detention centre staff are being trained in the use of capsicum spray, batons and restraint belts.

Ironically, all this occurred in the context of a general reduction in crime committed by young people in Victoria, and in the total number of young offenders. However, there has been a troubling increase in certain categories of violent crime committed by young people, most notably aggravated burglary and car theft.

These crimes are highly traumatising for the immediate victims, and they attract wide publicity, raising community concern and fear. Some have been committed by a relatively small population of repeat offenders. But other serious crimes have been committed by young people who had previously had little record of trouble with the law.

The cohort of repeat offenders seems easier to understand, with evidence that nearly half of the young people in detention had spent time in child protection. “The sad reality of clients in detention [is] that they are BOTH victims and perpetrators," former NSW Juvenile Justice Peter Muir said in his report to the Victorian Parliament.

For that other cohort of young people, who have committed serious crime seemingly “out of the blue”, a common factor seems to be that they have been expelled from school during a period of difficulty in their lives, “fallen in with the wrong crowd”, and “gone along for the ride”, For them, the need to belong overrides the need to do right.

This fits with conclusions reached by criminologist Don Weatherburn in his more than three decades with the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research: that young people who become involved in crime have poor attachments and/or poor associations. Repeat offenders have both.

Long-term crime reduction requires improving the conditions of family and community life. The criminal justice system should not undermine these efforts. Detention-as-punishment cannot improve attachments with carers. It runs the well-known risk of increasing poor associations. It doesn’t increase community safety in the medium- to longer-term, let along provide redress for victims of crime. So what’s the appeal of punishment?

Why governments promote detention

Governments promote detention for at least five reasons. One is a supposedly pragmatic argument: young offenders can’t harm the general public while they’re inside. Yet the evidence is consistent: the longer the sentence, the greater the likelihood that a young person will reoffend once they’re back outside.

That leaves the other four, to:

promote individual deterrence – “That will teach you a lesson!”

promote collective deterrence –“This should be a lesson to the lot of you!”

restore moral balance – “You’ll pay for this!”

exercise legitimate authority and provide an effective response to crime –“We’re in charge here, so we’ll deal with it!”

As it happens, punishment isn’t a particularly effective way to achieve any of these outcomes. It is not an effective way to teach or learn lessons about the impact of offending on others. Punishing offenders doesn’t provide redress for victims.

This inadequacy of punishment to achieve legitimate outcomes is a key reason for the growing international restorative justice movement.

Shifting towards restorative justice

An international base of evidence indicates that well-designed and delivered restorative justice programs can help victims of crime to recover, reduce the likelihood of people reoffending, and increase community safety.

Restorative justice involves the people who are most affected in determining an appropriate response to the harm caused by crime, via processes that can be used as an alternative to retributive justice, or as an adjunct. They offer a way to resolve the conflict between short-term politics and long-term policy in youth justice.

The preeminent example of “restorative justice” is the process of community conferencing, which is a meeting of a group of people affected by some common concern that is causing conflict. A youth justice group conference involves a facilitator supporting the group of people affected by a crime to recount collectively what happened, to reach a shared understanding of how everyone has been affected, and then to agree on what might be done to improve their situation.

While there is ongoing discussion about what precisely “restorative justice” means, experienced practitioners agree that a core element is “restoring right relations”. This is not some warm-hearted-but-soft-headed notion that “everyone gets along”. Depending on the nature of a case, relationships between participants in a restorative process may be restored or “set right” by:

- actually being “restored” [to something positive].

But relations may instead:

- simply no longer involve intense conflict [and thus “neutralised”]; or

- be formally ended [and so effectively non-existent], or

- be established [because some participants are meeting for the first time].

All Australia jurisdictions have adopted some form of restorative justice group conferencing, inspired by 1989 legislation in New Zealand and a pilot program in NSW.

Community conferencing continues to be used in youth justice to divert cases from court and to support judicial decision-making in court. In these applications, it delivers very high rates of participant satisfaction, including for victims of crime. It reduces reoffending relative to other interventions for equivalent cases. (The effect has been found to be particularly strong with crimes involving violence, and where community conference agreements address causes of offending.)

In addition to the original applications in youth justice and child protection, programs use community conferencing to support effective relationship management in schools and “conflict resilience” in workplaces. A small but growing number of programs also deploy restorative practices to address family violence and sexual assault cases. These programs have been controversial, in part because reformers struggled for years to have family violence and sexual assault treated as matters of public concern, and to have these matters addressed with adequate seriousness and consistency by the criminal justice system. However, many of these same reformers, having now listened more carefully to hear what victims of crime are actually seeking, and having observed what the criminal justice system currently has to offer, are themselves now advocating for restorative approaches.

How to put restorative justice to work?

Common to all these programs is a shift in how decisions are made, and who makes those decisions. The essential shift is from (i) a central authority imposing outcomes on people to (ii) an agency providing processes by which people who are affected by some common concern can reach a shared understanding, and can transform conflict into sufficient cooperation to negotiate workable outcomes for themselves. (Some reformers understand restorative justice as a re-emergence of traditional practices supplanted or repressed by central, and sometimes colonial, authorities.)

“Restorative justice” seems consistently to have been (mis)understood and implemented as something that should be delivered in stand-alone programs. The experience of many of these restorative justice programs, no matter how positively evaluated, is that they have then tended not to be leveraged by the rest of the justice system. So what can be done to ensure that opportunities to deliver restorative justice are leveraged by the rest of the justice system, rather than ignored by it?

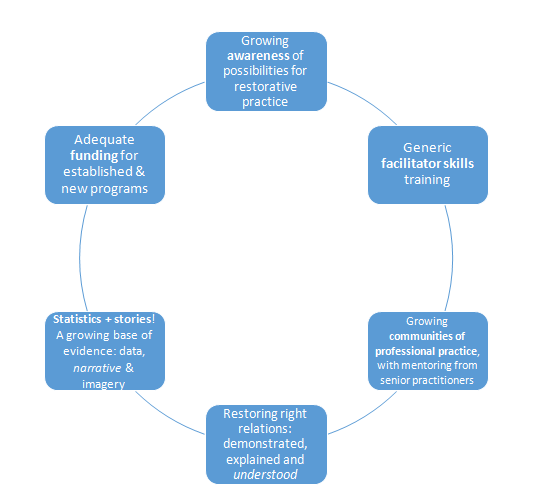

What types of organisation most effectively promote reforming ideas or support reforming practice? How do processes, programs, and principles (including social norms) mutually reinforce? More succinctly: How does a virtuous circle emerge?

In restorative justice, our current best answer to the question of how virtuous circles emerge is: through effective pilot programs which have the dynamic of an action learning processes.

Effective programs evolve through cycles of planning, initial implementation, review, reflection and revision, and this revision then enables the next phase of planning and implementation. Importantly, though, each set of lessons-to-date needs to be translated into changes to individual and organisational practice. And those changes need to be implemented not just within, but also beyond the initial program. Lessons from pilot programs need to be shared across a broader network of professional practice. We are now seeing this phenomenon occur in a structured, intentional fashion.

A case study and momentum

For just one (widely publicised) example: Victoria Police and other officials were highly impressed by the process and outcomes of a community conference held with some of the young people involved in and others affected by, the so-called Moomba riots of 2016. The Age journalist Emily Woods produced an accurate and thoughtful article on this event, with a headline proclaiming that this response to “the young Moomba rioters [was] restoring faith in justice.” Radio National’s Background Briefing program produced a similarly accurate program.

A subsequent conference dealing with a similar issue included traders and representatives from AfriAus care – a local support group with the motto “building bridges and strengthening community.” The principle of responding constructively and with dignity to social harm was illustrated when a local jewellery store owner donated $5,000 to launch a basketball team for young people of African heritage in Melbourne.

In just the last few years, there has been a proliferation of programs that realise the value of providing an effective process whenever and wherever a group of people need to restore right relations. Having long felt they were pushing against a retributive tide, many frontline practitioners now sense a turning tide. Vicious cycles of counterproductive-social-policy-exacerbating-ineffectual-practice are being counteracted by virtuous circles, such as this one:

Restorative justice practitioners and reformers are developing a better sense of this virtuous circle, where polices are mutually supportive, and evidence-based processes enable agencies to work with people, rather than doing things to or for them. “Working with” promotes social reintegration and therapeutic responses to trauma.

However, those of us working in this field must clearly and consistently explain how this approach works to respond to problems, prevent their recurrence, and promote social flourishing.

And with some luck, our clear and consistent explanations can help policy-makers align effective short-term politics with responsible long-term policy.

Members of the Victorian Association for Restorative Justice will discuss these recent developments during Restorative Justice Week (November 19-26) at a presentation and panel discussion at the Law Institute of Victoria, on 23 November in Melbourne.

David Moore is current President of the Victorian Association for Restorative Justice. He is also Principal Consultant with Sydney-based Primed Change Consulting and is consulting to the Commonwealth restorative engagement and redress schemes.