Australia falls behind OECD on paid parental leave

Labor has recently announced it is looking to Nordic countries for inspiration to overhaul Australia’s Paid Parental Leave scheme, which has been called out for being miserly compared to Australia’s OECD peers. Advocates say changes to the scheme could reduce the carer and housework gender gap, increase parent-infant bonding, reduce the gender pay and Superannuation gap, and improve overall health and wellbeing for families. In today’s analysis, Belinda Townsend (@BelTownsend) and Lyndall Strazdins, both of ANU and the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence on Health Equity (@crehealthequity), provide some history and context for how the Paid Parental Leave Scheme came to be, outline some of its strengths and weaknesses, and provide guidance for how to improve it going forward.

Paid parental leave is important

Supporting parents in caring for their infant reaps long-term health and wellbeing rewards - but Australia could do much better. Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash.

Australia’s first national paid parental leave (PPL) scheme was announced ten years ago on Mothers’ day in 2009. It meant that the primary caregiver (either parent) is entitled to eighteen weeks government-funded pay at the minimum wage. In 2013 an additional two weeks ‘dad and partner pay’ was added, also at the minimum wage. This freed many parents from the financial dilemmas of taking time after a birth to recover and care for their baby without an income, many of whom had no access to employer funded parental leave. Australia was the second-last OECD nation to implement a national PPL scheme.

PPL has made a major difference - not just to a family’s financial survival but to parents’ and babies’ well-being. The first six months after birth is critical for how children develop, and for parents’ well-being as well. PPL also supports parents in combining jobs with care, a boon to the economy and to equality. Evaluations of the scheme have shown that the PPL delivered. There have been improvements for women’s labour force participation and for maternal and child health, especially for women in low paid work. Nevertheless, Australia still lags well behind other OECD countries on the length and amount of paid leave available for parents, with growing class and gender inequities.

Australia compared to the OECD

The OCED Family database illustrates how Australia is falling behind other OECD nations on a number of measures for PPL.

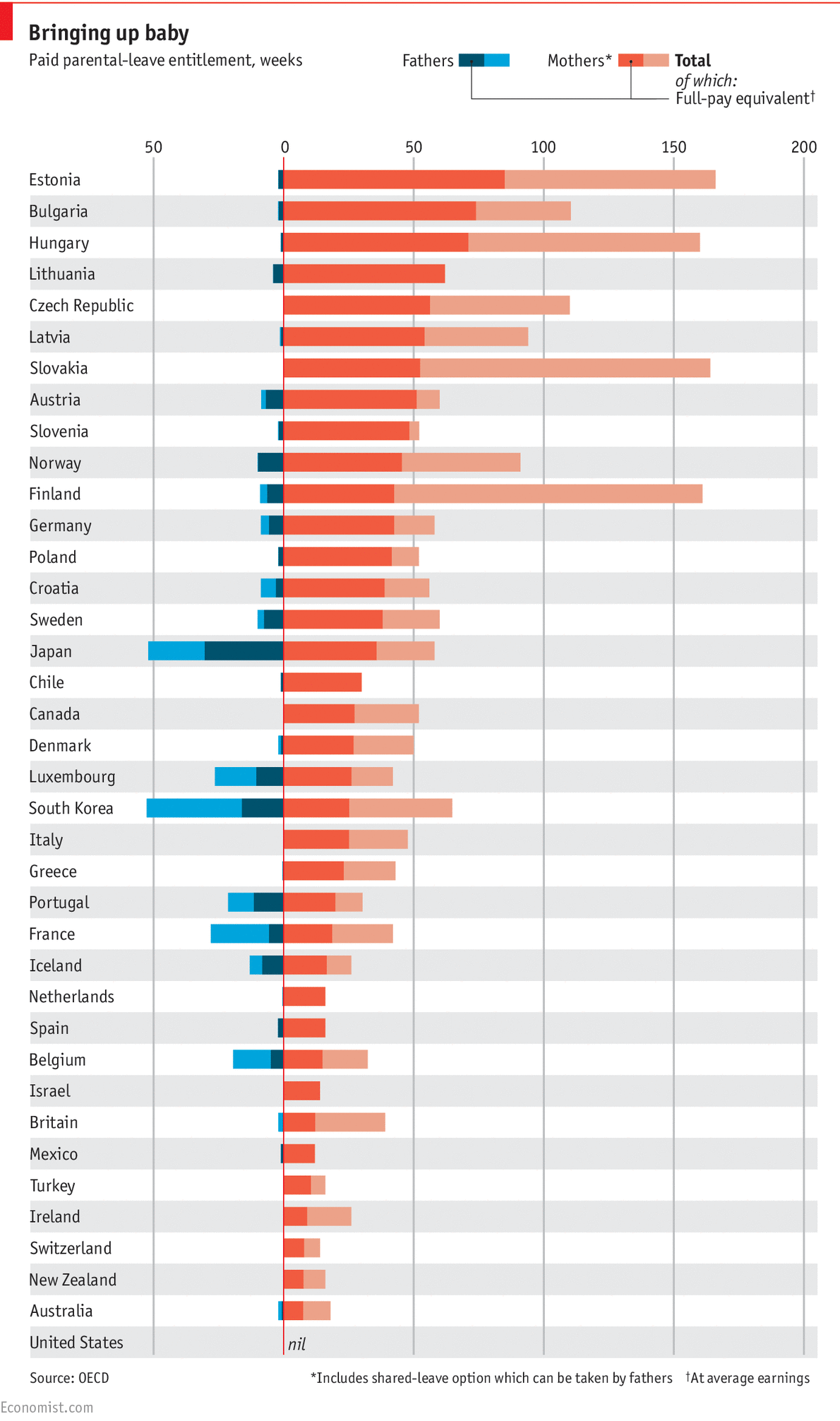

OECD comparisons of Paid Parental leave. Australia lingers at the bottom of the pack. Graph from The Economist.

First, the length of available paid leave (both maternity and parental) in the OECD is, on average, 53 weeks for mothers and 8 weeks dedicated leave for fathers. This is generous when compared to Australia’s government-funded leave, which provides 18 weeks for the primary caregiver, and 2 weeks dedicated to fathers.

Second, compared to other OECD countries, Australia’s public expenditure on PPL is much less - less than half the OECD average of US $12,000 per live birth.

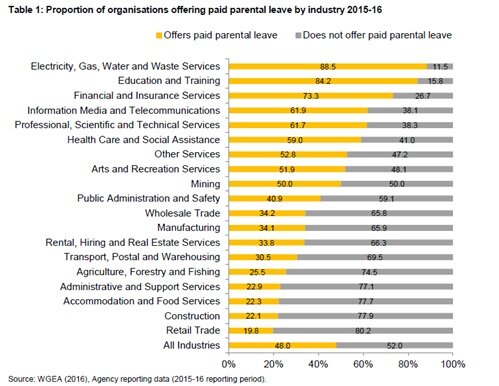

This gap can partly be explained because Australia has a hybrid scheme, with expectations that employers will voluntarily provide employer paid leave in addition to the government-funded scheme. However, ten years on, more than half of employers in Australia provide no additional employer paid leave. This creates large gaps in coverage which directly impacts families and children’s well-being.

There are significant differences by industry sector in what employers offer. For example, WGEA shows that while more than 70% of financial sector employers offer some form of employer paid leave, more than 80% of retail trade offers no employer paid leave. This deepens class and income inequities amongst Australian families. It leaves behind those on low income or in low-paid jobs which are the families that desperately need support.

While nearly half of organisations offer some form of Paid Parental Leave, it is heavily skewed by industry, reinforcing economic inequalities. Graph credit: WGEA.

As a result, many families in Australia can only access the eighteen weeks at the minimum wage, which is below the World Health Organisation’s guidelines of 26 weeks for optimal infant breastmilk feeding. This creates inequalities, at birth, for Australian babies that could play out in their health and well-being throughout their lives.

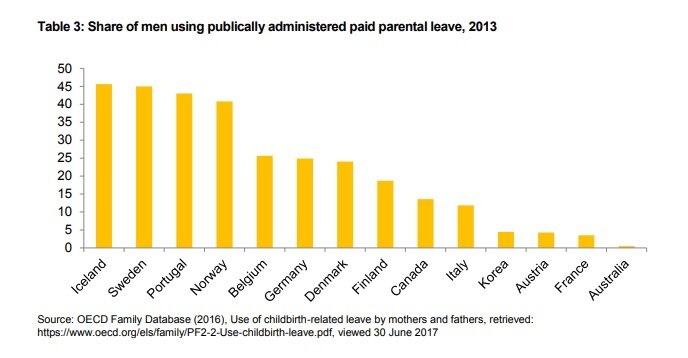

Finally, the scheme inadvertently reinforces gender inequities in caregiving. In most families it is women who use the government-funded scheme, for many reasons. However the options for fathers makes it almost impossible for these men to take significant time from their jobs to bond with and care for their baby. There’s almost no incentive in the current scheme to help or encourage fathers and the WGEA reports reveal what a deficit that is. It shows that when PPL is available men are more likely to take it, and employers play a key role in normalising parents’ utilisation of PPL and of flexible working arrangements for families.

Lessons from agenda-setting

Men are often losing out on Paid Parental Leave - due to a mix of policy limitations and cultural norms. Graph credit: WGEA.

Our new research, published with colleagues in Health Promotion International, investigates why Australia was one of the last OECD countries to have a PPL scheme, what led to policy change, and how health emerged as a key policy goal. This qualitative research was based on document analysis and twenty-five semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders intimately involved in the agenda-setting and policy processes for Australia’s PPL scheme, including politicians and political advisors, trade unions, public servants, industry associations, civil society and academic experts.

We identified two phases in the advocacy for PPL in Australia; the first between the 1970s and 2000s where PPL failed to get onto the agenda, and the second from 2000 onwards when there was a significant shift in tactic and the eventual policy announcement.

The barriers that policy advocates encountered in the first phase were structural, ideational and institutional. First, Australia’s welfare state emerged through a particular male breadwinner model which prioritised men’s employment and historically neglected women’s work. This model has continued to serve as a barrier as public policy has not kept up with changing family and societal attitudes to PPL.

Second, maternity leave was seen as a private right to be negotiated between employers and employees in an adversarial industrial relations environment. Our analysis showed that employers were (and many still are) opposed to paying maternity or parental leave and did not see this as a workplace responsibility. Until the 2007 election of the ALP, socially conservative ideas about the role of women in the home still prevailed and held sway both in Parliament and in (some parts of) the community. This all dovetailed with the neoliberal idea that it was essentially a private and individual decision and responsibility, not the market’s or the government’s. These were arguments that were hard to contest, especially because the evidence base for the benefits of paid parental leave had not been built.

From the early 2000s, after years of resistance to PPL in the industrial relations venue, advocates shifted tactic to a government-funded scheme with a voluntary employer top-up. To secure this scheme, advocates used multiple framing strategies, positioning PPL as a benefit to health, to gender equality, to economic productivity and to population growth, as well as building evidence on the ‘business case’ for employers of keeping employees.

Through these framings, advocates in government, women’s organisations, and trade unions built up a broad coalition of supporters, including supportive industry associations. Academic experts generated the evidence to support a scheme, and advocates strategically shifted the issue into the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission and later the Productivity Commission, in order to open the wider discussions of the benefits of PPL for society. By the time the ALP won the 2007 election, many were already on board and ready to adopt a scheme evaluated by the Productivity Commission.

Our analysis reveals broader lessons for agenda-setting for action on the social determinants of health. It highlights the value of using multiple framings and forming broad coalitions that criss-crossed different perspectives and interests with policy allies. We found that all three frames – for economics, gender equality and for health were required to advance PPL, and that in combination they built the coalitions and shifted the issue into venues that policy would eventually act on.

Next steps for PPL in Australia

Our interviews also revealed that those involved in crafting, steering, advocating and building the PPL scheme always viewed it as the first but not the final step. It was seen as the beginning, the precedent and the foundation to advance a scheme that could fully deliver on health, equity and economic goals.

Importantly, the first scheme demonstrated the power of investment in this critical period after the birth of a child. There was no economic disaster or disadvantage – the opposite occurred in fact. The first 10 years of PPL has shown that most of the objections and concerns raised can now be laid to rest. There is no evidence of harm, only benefits.

So the question is what might the next steps be? There are quite a few possibilities here. One option would be to extend the length of leave and increase the income paid to parents so it is closer to the OECD average, through extending the government scheme or employer paid leave or both, or a levy. This would also ensure all babies and parents have both the time and financial support to optimise breastmilk feeding, parent-infant bonding and address income inequalities. Another option (and these are not exclusive) is to increase father-dedicated leave, again either through government funding or employer schemes or both, giving fathers the support and validation to take more time off. Reviewing compulsory superannuation in employer leave payments so that later life savings are not compromised by leave would also be an important addition to the scheme (recommended by the Productivity Commission in 2009). The options are numerous but the policy advocacy, framing and coalitions are needed to make further improvements for Australian families.

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury @GoodAdvocacy