Straightjacketing evaluation outcomes to conform with political agendas – an examination of the Cashless Debit Card Trial

The Cashless Debit Card Symposium was held at both the University of Melbourne and the Alfred Deakin Institute on Thursday, the 1st of February 2018. The Power to Persuade is running a series of blogs drawn from the presentations made on the day. In this piece, Susan Tilley of Uniting Communities shares the findings of a discourse analysis of the ORIMA evaluations of the Cashless Debit Card Trials (CDCT), reporting that the evaluations are deeply imbued with government ideology.

This article provides a summary of a longer study that explores the interplay between government-commissioned evaluations of its own social policy programs – using the example of the Trial of the Cashless Debit Card (CDCT) in South Australia and Western Australia – and the factors that inform such transactions.

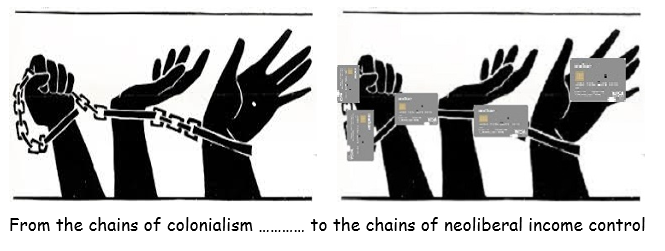

The central tenets of the Government’s current attitude to those needing income support were examined using discourse analysis. The findings highlight the continuity of the colonial project and its manifestations in the current neoliberal ‘welfare reform’ agenda.

According to the Federal Government, the CDCT was introduced in order to “reduce the social harm caused by welfare-fuelled alcohol and drug abuse and gambling” (p. 3) by reducing the amount of cash available to people. The 12-month trial was evaluated by ORIMA Research, which produced three reports, published in February (Wave One), March (Initial Conditions) and August 2017 (Final Report).

Evaluation transactions

There is an assumption that professional evaluations are conducted with both neutrality and objectivity. However, program evaluations are conducted within a political context and are shaped by implicit and explicit factors, including:

· the program being evaluated is itself a product of political negotiation;

· selection of the evaluating agency is usually based on the congruence of the norms and values of the evaluator and those of the commissioning party;

· value-laden terms of reference and funding arrangements may include conditionalities;

· the evaluator’s norms and values are consciously or unconsciously brought to bear on the subject of the evaluation;

· the inclusion or exclusion of community participants; and

· the ways in which evaluation outcomes are framed and selectively emphasised.

Our study concludes that the ideologically-driven use of the evaluation findings has resulted in negligible positive change for people experiencing socio-economic and structural challenges, and has instead caused a deterioration in their circumstances.

The CDCT and its evaluation is imbued with a particular end-game in mind. The ideological imperative to arrive at a particular set of decisions about the CDCT and its evaluation has been driven by the commissioning party – the Department of Social Services – from the planning and design of the program, through to its commissioned evaluation by ORIMA Research, and the selective use of the evaluation findings.

Ideological expressions

The analysis of the CDCT, the associated evaluation process and selective use of its findings, reflects a world view that is premised on a set of understandings about the cause and place of poverty and unemployment in society. These understandings reflect a continuity from settler-colonialism through to the current expressions of neoliberalism and attitudes to those needing income support.

Understandings of poverty, blame transference and infantilisation

The neoliberal extension of the colonial narrative views poverty as the result of a moral, behavioural and individualised deficiency, thereby justifying the state’s abdication of its responsibility to provide adequate social security.

The individualisation of poverty and treatment of citizens as ‘consumers’ with ‘mutual obligations’, denies the structural nature of unemployment and inequality, and ignores the lack of a labour market and the shameful history of dispossession and the fracturing of families and communities. The denial of these realities enables blame transference, away from the State and to the individual who is experiencing socio-economic hardship. This ‘blame game’ enables the State to view those needing income benefits as incapable of managing money and in need of patronage, primarily through limiting their access to cash payments. In the process, recipients are infantilized in ways described by Frantz Fanon in his work on colonialism[i]. Comments provided to Uniting Communities by Ceduna residents who are on the CDC illustrate this:

“We’re starting to feel like we’re back in the ration days when white people managed our lives and everything else and treated us like children. It’s the same now. We’re treated like children and so we can’t make decisions for ourselves. We’re moving backwards, not forwards. We want to make our own choices and not be treated like children. ”

Homogeneity

The CDCT has been imposed in a mandatory and uniform way across all on income support and the State has presented the community response to the Card as a homogenous one, thereby glossing over and failing to register the articulated and differentiated responses of community members which contradict its own prescriptive narrative.

Erosion of rights

Through individualising poverty, infantilisation, and treating recipients as an artificially constructed homogenous grouping, people’s human rights have been eroded. The lack of community consultation about the design and implementation of the Card is a breach of the right of Aboriginal peoples to self-determination and flies in the face of Article One of the International Covenants on Human Rights, and the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which require meaningful consultation with and the informed consent of Aboriginal peoples during the development and implementation of policies and laws that affect them. The violation of human rights and racialized exclusion of Aboriginal peoples through the enforcement of income management illustrates the extent to which colonial reasoning and practices are embedded in the State’s current neoliberal agenda. The Australian Human Rights Commission stated in February 2018 that the CDC raises concerns “about the non-voluntary nature of the card, and its compatibility with human rights standards, specifically the right to social security, the right to a private life and the right to equality and non-discrimination.” (p. 17)

Structural violence

The unidirectional, ultimatumist approach on the part of the State can be described as structural violence. Rather than addressing structural inequality and poverty, the State has resorted to using punitive instruments of structural violence; these have resulted in psycho-social and economic harm and potentially long-term damage to individuals and future prospects of reconciliation.

The continuity of the colonial project

The ‘modernised’ neoliberal welfare conditionalism through mechanisms such as the CDC, with its increased level of intervention, and blanket application, reinforces the old patterns and mechanisms of colonial control. As Hondius states, ‘Coloniality continues but it is now dressed up in the clothes of neoliberalism’.[ii] This continuity of the colonial project is best described by Susan Haseldine, a Ceduna resident and elder, in her response[iii] to the introduction of the Card:

“What our mob just said was, “Why didn’t you just put the chains on us again?” That’s how they felt.”

Social return on investment?

In the context of the Government’s repeated refrain about fiscal constraint, it sees fit to implement a punitive program that is costing a great deal to administer, with a negligible social return on investment. As at May 2017, the estimated cost of administering the Trial was $18.9 million with an average cost per person of $10,000. A cost-benefit analysis of the trial evaluation indicates that the expenditure of $18.9 million has only received a positive indicator – albeit limited – from 407 of the total 1,850 participants. Given the negligible benefits of the Trial, aside from the negative impacts on participants, the Government’s intention to roll out the Card to additional sites appears reckless and points to the ideological imperative that is driving this punitive welfare ‘experiment’ at any cost.

Conclusion

Despite opposition from communities, and acknowledgement by ORIMA Research regarding the limitations of its own evaluation data, the Government continues to pursue its plans to extend and expand the application of the Card, while asserting that this will only be done in conjunction with communities. Community opposition (see also here and here) controverts the Government’s publicised view that communities and leaders support the Card, and puts into question its use of this view to justify the Trial’s extension and expansion.

In the face of the seemingly intractable challenge of structural poverty and unemployment, government policy-makers appear to lack the ability to develop comprehensive and systemic responses, and instead repeat bureaucratic and punitive ones that serve to blame those experiencing socio-economic challenges and then control them by means of archaic behaviour-modification strategies.

The Australian Government’s determination to justify, extend and expand the Card to further locations is driven, not by a sound evidence base or informed by genuine consultation, but by an ideological imperative and a particular view of citizens who require income support.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

To read more from the Cashless Debit Card Symposium, see:

The mounting human costs of the Cashless Welfare Card

Human rights and the Cashless Debit Card: Examining the limitation requirement of proportionality

My experience of the Cashless Welfare Card

Looking at the Australian social security system through a trauma-informed lens

Financial inclusion, basic bank accounts, and the Cashless Debit Card

[i] Examples of Fanon’s work on this topic include Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth.

[ii] Hondius, D. 2014. Blackness in Western Europe: Racial Patterns of Paternalism and Exclusion. Routledge.

[iii] Gage, Nicola. ABC News article. Ceduna’s cashless welfare card a ‘massive inconvenience’ but council sees improvements. 12 September 2016.