Couch-surfing Limbo: “Your life stops when they say you have to find somewhere else to go”

Homelessness is a rising problem in Melbourne, and escaping family violence is the single biggest reason that women and children experience homelessness. For many homeless children and young people, though, the problem is masked by high rates of couch surfing. In today’s blog post, Shorna Moore of WEstjustice and Kathy Landvogt of Good Shepherd Australia New Zealand share preliminary findings from a couch surfing report due to be released by WEstjustice in 2017. This blog is based on an article that recently ran in Parity.

Youth homelessness and couch surfing

Couch surfing is the dominant way that young people experience homelessness, crashing on a friend’s couch to avoid returning home or being out on the streets, and often moving frequently. Yet it is largely a hidden problem. In fact the ABS has not yet established a reliable way of estimating homelessness among youth staying with other households, with the definition unclear as to whether it involves days, months or even years. Despite an under-estimation, however, the census data still reveals that youth aged 12-24 years are over-represented in the homelessness population, accounting for 25% of all homeless people in Australia in 2011.

Problems at home, including family violence and conflict, are usually the drivers:

“I was running away from family. Dad was very scary, for sure there was mental and emotional abuse. It wasn’t mum, she copped it as well and she was avoiding home”.

Young people and even children turn to shelter offered by friends, friends’ parents, family and sometimes strangers. As one couch-surfer said, “I would go anywhere”. However, these temporary living situations tend to be unsustainable and potentially unsafe:

“If you are loitering around you meet people and someone will offer you somewhere to sleep.”

Investigating the Issue

WEstjustice is undertaking an action research project to explore the experiences of young couch-surfers in western Melbourne and their couch-providers. Legal clinics provided legal advice and assistance to couch surfers aged under 25 at targeted outreach locations including schools, welfare agencies and emergency houses. These clinics formed the basis for further exploration. We believe this is the first time that the place of the couch-provider within the homelessness sector is being systematically examined in Australia.

The research includes a literature review, case data from 62 young people assisted, in-depth interviews with 6 couch-surfers and 6 couch-providers, and consultations with 30 practitioners including lawyers, youth workers, alcohol and drug workers, social workers, school staff, cultural officers, and government representatives.

The data is currently being analysed and a report will be published in 2017. Preliminary findings presented below address three questions: the characteristics of couch-surfers, the characteristics of couch-providers, and the risks and benefits of the couch surfing relationship.

Who is sleeping on the couch?

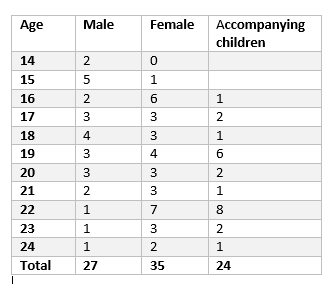

62 young people were seen in the Couch Surfing Legal Clinic. Ages ranged from 14 to 24. Many young people revealed that they started couch surfing as young as 12 years old. A significant group were single mothers. A total of 24 babies and toddlers were identified through the project. Fourteen of the single mothers had left their house due to family violence.

Table 1: Age and sex of participants in couch-surfing project.

Some schools estimated up to 30 students at any one time couch surfing. These students were physically and emotionally exhausted (some getting only four hours sleep a night) and often hungry.

“It really impacted on my school, especially the TAFE I did once per week. I was exhausted.”

With no money for clothes and no access to washing machines, personal hygiene was reported to be an issue. From the perspective of the couch-surfer the problem was all too clear:

“I didn’t have any clothes of my own. I only had enough clothes for about 3 days of the week. My friend would sometimes lend me his clothes but basically I lived in those three outfits for the year.”

Students encountered additional difficulties at school:

“Whenever I got to school I didn’t have the right school shoes and had to wear my runners. I’d always get suspended.”

“I’d find it really stressful when I had to do assignments. I couldn’t do it because I’d always be trying to find somewhere to sleep.”

Attending school in these circumstances takes commitment, but paradoxically many needed to couch surf precisely because they did not want to leave the local area until they finished secondary school:

“I did have hope. I know that I’m smart and can actually do something and it was upsetting and depressing to know the position I was in”.

Additional vulnerabilities were identified including young people with disabilities and refugees placed in the community without stable accommodation after leaving detention centres.

Whose couch is it?

Couch-providers are the unknown element of the relationship. The study has identified four broad categories: friends, parents of friends, family, and strangers.

Many couch-providers such as a friend’s parent or caring community members genuinely want to help, providing a roof, food, care and safety:

“I treated him like any of my kids. I gave him money for his Myki, my last $5. I made sure his clothes were washed, had food, showers and internet. I felt that was my responsibility because I took him in.”

“The majority of the people that I have had stay I didn’t actually know beforehand. My daughter would call me and say “a friend can’t go home tonight, has a family situation, can they come to our house?”

These couch-providers have no support helpline, service, or information about their rights and responsibilities. Many feel unsure about how to assist with family violence, medical, trauma and legal issues. Many cannot afford the extra cost involved:

“I’m already a single mum with three kids... Just putting another mouth in the house to feed, I felt the pressure during the 4 weeks. I had to break into some piggy banks… take money to give to him.”

Even positive couch surfing relationships frequently break down under the strain.

Unfortunately there are also couch-providers who are involved in crime, drugs, prostitution and illegal rooming houses, exploiting and abusing couch-surfers for their own ends. Couch-surfers often encounter these strangers at the local train station.

Couch-providers are all responding to deficiencies in the homelessness sector in some way: benign couch providers are subsidizing the homelessness sector; abusive couch-providers are exploiting a service gap. This research found that in many cases the responsible authority (DHHS) does not respond to the housing needs of mid- to late-teens:

“I asked the social worker to talk to DHS. DHS wasn’t really interested.” (Couch-provider)

What is happening on the couch?

Couch-surfers are exploited in many ways. Some couch-providers get the Family Tax Benefit instead of the parents, promising to buy food and essential items but then reneging on this promise. Some are ‘in the business’ of taking young couch-surfers in, tricking the school into supporting applications to Centrelink. There were also other types of economic exploitation:

“I stayed in the house for the whole 3 months, doing housework. They didn’t let me leave the house. I did it because she was paying for the food. I asked to go to Church on Sundays but they wouldn’t let me go.”

Drug dealers get young couch-surfers to live with them to watch over the crop and sell the drugs to younger friends, including targeting schools; in return they are given free drugs, board and food.

“I was made to go down and drop it [drugs] off to people…because I was staying at the house. I’d get a feed every now and again. I wasn’t involved in it at all before I started couch-surfing. I got a bad heroin habit, it was disgusting.”

Sexual abuse of young female and in some cases male couch-surfers was common. ‘Sleeping on couches for sex’ or being forced into ‘more serious relationships’ also led to sexual abuse and unplanned pregnancies.

“I experienced lots of violence while couch surfing. You can put yourself in positions where there are people you never met before and you can be put in a very awkward position because they were men.”

“I was sexually abused two different times couch surfing by two different people. The first time I was 13 and the second time I was 16. When I was 13, he took advantage of me because I was alone. I wouldn’t have stayed there if I was living at home. It was just somewhere to sleep. When I was 16, I was couch surfing at this guy’s house. One day he took me to this remote place to his grandma’s house. His uncle lived down the road and it was him that did it. I didn’t press charges I suppose ‘cos of the situation I was in [couch surfing].”

Young parents understood this was not a good environment for infants:

“When we couch-surf she was watching more and taking more notice of what was going on and who was there. Whereas when she’s at home she’s a lot more comfortable with anyone that walks inside.”

Even in positive couch surfing situations, there were challenges. Providing food, transport, washing, emotional support, and opening up their home often put undue pressure on couch-provider families, including other children in the home:

“I did find it challenging. You could see my family getting more and more tense as well.” (couch-provider)

This de-facto ‘care giver’ or ‘informal foster parent’ role is especially challenging as many of the couch-surfers have experienced trauma and have behavioral issues:

“For me it was a bit blurred. I didn’t know whether I was there as a social worker or a friend’s mum.” (couch-provider)

If babies and toddlers are involved, the parents of the couch-surfer may still be collecting the Centrelink Family Tax Benefit while the couch-provider is the one caring for the couch-surfer.

What needs to change?

The final research report will provide further analysis and recommended actions including:

· Early intervention in schools, for example through school-based lawyers;

· Support and assistance to maintain good couch surfing arrangements/relationships;

· Targeted services and safe spaces for couch surfers;

· Education and assistance for couch providers; and

· Law reform including social security, fines system and discrimination laws.